Greg Egan’s near future sci-fi novel Zendegi centers on a moral dilemma, potentially solved through technology. Martin, a single father raising his young son Javeed in a newly democratic Iran, discovers he will soon die and has to arrange for the rest of his son’s upbringing. He doesn’t have any family, and doesn’t trust his son’s godfather to instill the core values of life. So he arranges for an experimental training process to create an imperfect but functional virtualized neural double of himself that can guide Javeed during play sessions of their favorite virtual reality game, Zendegi.

Martin rarely doubts his course of action, but the reader has to ask the question “would I do the same?” In most sci-fi novels, such questions can be indefinitely deferred, we never have to answer questions about cloning or time dilation, but our world is different. The neural imprint process featured in the novel may still be far off, but a more minimal version - say a chatbot that accurately represents (with 85% accuracy) what a dead person involved in its training might say - is either already or imminently possible. This is a decision I will have to make: do I want to make a digital copy of myself to advise my future children after my death?

My immediate reaction is a swift “no,” because such a bot will not be me. It will not accurately represent me completely, and the parts that are imperfect may be very serious distortions.

But the real problem is that a bot is pretending to be a dead person. Through its interface and design, it recreates the experiencing of talking with another person through a text medium. The minimalism of text conversations, like the screen in the imitation game that Turing based his test on, ends up serving as a sort of shield to protect the illusion. Because I cannot see their face, I can pretend the dead are still alive and able to talk to me. Texting a bot recreates almost exactly the experience of texting with a living, breathing human. And even if I do not explicitly believe there is a person on the other side, the experience is based on that illusion. And that illusion is immoral, deceiving the human user and disrespecting the absent partner.1

Nearly all chatbots abuse this illusion. Conversation is not a neutral interface for information delivery, because conversation is an emotionally charged pat of human interaction. Up until this point, every conversation had by humans has been with other humans, and it is our primary method of social interaction. If someone were to say something incorrect about me, that would be a mistake of information. But if a chatbot copy of me were to say the same incorrect fact in the first person, that is a deeper deception.

The text interface uses illusion from depriving conversations of image and voice, but the imminent technology which will perfectly mimic these aspects of human interaction makes an even more dangerous illusion. The AI-powered chat app Replika began as a project to resume conversations with the creator’s dead friend, but has now transformed into a 3D embodied character who carries on an eerie relationship with its users, replacing more intimate human connections.

But pure information seeking need not masquerade as something else. Information about what the dead would have or might have said is useful and frequently sought out. One can imagine that a man who has lost his father contemplating an important decision might ask his father’s friends and loved ones what he might have thought. A memorable moment for me was being told by my father that my long-deceased grandparents would have proud of me, a moment made far more potent by the fact that he was speaking from a position of knowledge. Reading through an admired person’s writings or letters to better discern their thinking can be an incredible act of love for the now dead.

There are plausible ways that AI could be a part of such processes without abusing the illusion of resurrection. The interface need not be in the first person. If a conversation is truly necessary the persona the AI takes on might be a researcher who has read texts and analyzed data, but lacks certainty about what the person would actually have said or thought. Even better, simply create an interface which allows the user to encounter the actual recorded words and memories of their departed loved one and make the insightful connections themselves.

I hope that I might provide the most guidance possible to those I love, and if AI is a tool that can assist that, I hope it will be used. But illusions provide no guidance and leaving such a ghost would likely do more harm than good.

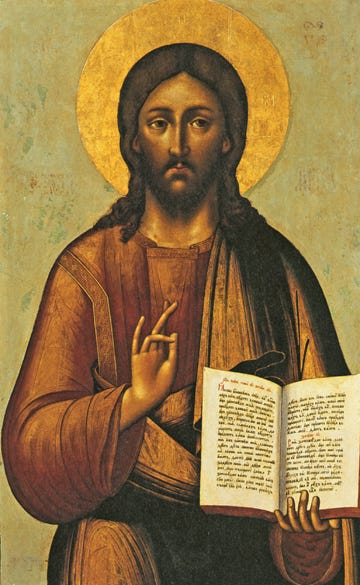

In parts of the Islamic world, there has traditionally been a great concern with images of God’s fine creation. The prophet and his companions, humans, and animals, all deserve respect in different orders. Images of the prophet must not be mistaken for the polytheist idols Islam was replacing. Eastern Christianity had its own disputes over images, eventually letting icons win out over the puritan suspicion of images, but icons with their own ideology of purity and respect for their power. Any change to something so powerful is treated with extreme caution.

Humans are drawn to images and eager for gods. As the Israelites quickly made the Golden Calf while Moses was away on the mountain, we moderns are rushing to give any sort of conversational technology the emotional power of a living entity through the illusions of artistry. Yet as the followers of the God of Abraham have shown, one can respect the power of gods without forcing it into an idol.

As morality is situational, there are situations where this might be acceptable.

So insightful, thanks