Bollywood is Better

In America, disliking musicals is a fairly common cultural stance. Musicals are middlebrow, they are not placed on the same cultural altar as Oscar-winning films, and certainly not on the same tier as inaccessible art like Classical music or high literature. But their dedicated fans are educated enough that their likes are not low-brow or merely dismissible as “pop” either. Occasional hits like “West Side Story” or “Hamilton” break through the noise, but mostly the genre continues as a cult interest. Beyond musical theater, the style makes its way into film largely through animated movies targeted at family audiences where it retains the same aesthetic characteristics and ultimate cultural fate.

America has the best funded and most active entertainment interest in the world, so one would expect its achievements to be the limits of commercial entertainment. But in terms of musicals, India1 has surpassed it. Film music, which evolved from earlier local theatrical traditions, is enormous in India, dominating the music industry as a whole and guiding the success of the most popular films. And filmi songs are, as a whole, better and more interesting than the songs of Western musicals.

Someone who doesn’t like musicals might expect to not like Bollywood films, which are largely musicals. But this judgement is often an error. Bollywood music is fun, danceable, varied in genre and mood, and can be enjoyed separately without the context of the plot of the film. The dancing is better, the singing is better, it’s all better.

People can develop personal likes and dislikes based on experiences and memories, and these are two enormous genres, so it is not as simple as I’m saying. But this isn’t entirely subjective either. These are two entirely different tradition which now occupy parallel niches in culture, and one has desirable features which the other lacks. The reasons for this emerge from the historically defined structures of each genre, and revelation of those structures show the paths too alternatives.

Musicals in America media, both on film and the stage, come from a wide range of pre-mass media entertainment. Music halls, vaudeville, and minstrel shows all provided the masses with music in a definite low-brow contrast to the more aristocratic pursuits of the 19th century such as opera and orchestral music. They used the shared instrumentation of European-American culture to accompany these performances - violins, horns, etc, and made many songs which were entertaining and popular. Notably absent from this tradition is percussion: percussion was still primarily used for military purposes or for related festive occasions such as marches.

With the great lifting of popular culture via the money of Broadway comes musicals proper. Rather than a long sequence of anonymous compositions by forgotten performers, the first proper popular composers enter the scene composing both show tunes and standards that would grow into the great American songbook. These composers were by profession and training composers in the Western musical tradition. This meant that they wrote sheet music and used the piano to make multi-part harmonies to accompany melodies following the rules of part-writing that had been standardized several centuries before.

The need to share written music with ensembles of performers efficiently allowed composers to rise to this role rather than for example band leaders or individual performers modifying and teaching the music based on each performance. And the music portion of the public education system of the United States ensured that the musicians and singers would be familiar with reading sheet music and the various paradigms of notes and rhythm. While the earlier vaudeville could include many kinds of performers, this composed music placed musicals in a different cultural realm. Blues was not in musicals, spirituals were not in musicals, jazz was not in musicals. If these genres were incorporated, they were incorporated using the proper western instruments for a musical hall with proper singers (proper both in education and, inevitably, race). As entertainment with trained performers and written scores, musicals were able to level up their status to the middle brow. At least in America, they became acceptable entertainment for the upper class as well as their inferiors.

This was where musicals stayed. They were not able to become avant-garde and surrender the popularity that made their production possible, nor could they sacrifice their credibility by lowering the musical pedigree back to the untrained domains of folk performance. The advent of sound films and the lavish budgets of Hollywood brought the musical into a golden age, but changed little. Hollywood took its music and talent from Broadway, but by an emerging convention the performance and sound changed little, the goal of a good musical movie being to copy the successful stage production.

A steady talent of composers and performers trained for the job of producing popular music based on the standards of Western music education kept the system going and produced certain heights and individual successes, but little motion for the genre itself. Rogers and Hammerstein, Stephen Sondheim, Leonard Bernstein all have made significant achievements in this style, but the style itself is static and reached its maximum appeal and creativity long ago. Disney continues to produce entertaining music for the generations for whom everything is new, and a disinterested public is occasionally swayed with jukebox musicals which simply supplant the genre with popular songs from other traditions. Musical composers try to overcome their constraints by including instruments and styles from other genres, but to remain musicals they must keep their same focus on choral harmonies and composition. Andrew Lloyd Weber incorporates electric guitars from rock and Lin Manuel Miranda replaces verses with raps but these are surface additions to the same musical backbone. Western pianistic harmony cannot be challenged, and so the genre stays in the same place.

India is not bound by this history, and with its own set of constraints and influences produced something new and worth learning from. Greater South Asia was home to many indigenous theater traditions, but it was several which saw their heyday in the late 19th century that were to inform Bollywood. The popular urban theaters including the Marathi and Parsi theaters took plots from South Asian tradition and Shakespeare and performed them with music drawing from folk and light-classical traditions. When those in Hindi-speaking regions began to make commercial sound films in the 1930s, these were the performers and musicians who created the genre now know as Bollywood.

In a different modernization process, films quickly overtook the stage as the primary medium for musical drama. Indian filmmakers were therefore able to uniquely leverage the technological and practical benefits of film over live performance. Non-sync sound allowed for the high quality recording of songs separate from performance, and quite quickly the first generation of actor-singers were replaced by a more efficient division of labor: actors who could dance, and playback singers who just had to sing.

Playback singers are an incredible benefit to Bollywood’s music. Typically they are trained according to Indian classical standards and have extremely long careers over which they are able to master any genre as necessary. Where Western singers (especially women) are confined to singing for characters who strictly match their age profile, a 70 year old Bollywood singer can skillfully go between the roles of an 18 year old and 50 year old, and perform better than both. This allows the actors themselves to focus only on dancing, which they do extremely well.

Lata Mangeshkar performing in her 30’s as Waheeda Rehman in her 20’s.

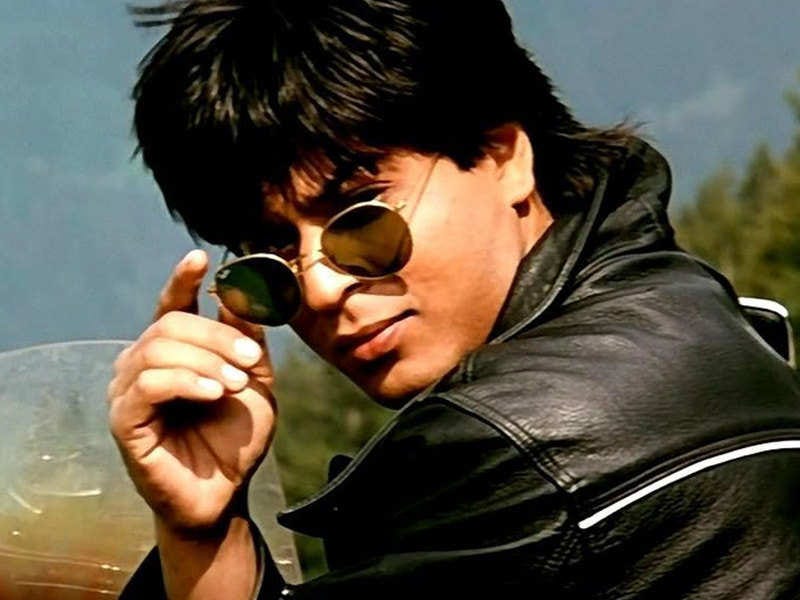

Lata Mangeshkar performing in her late 60’s as the 20 year old Kajol.

But far more important than playback singers is the generic and musical flexibility afforded to Bollywood music directors, a role without a real equivalent in America. Musical directors tend to have training in multiple traditions, coming from family lineages in some form of Indian classical music and then receiving additional training in western harmony and orchestration. They can make scores and songs that use classical Hindustani motifs on a sitar, feature as a base booming percussion drawn from India’s rich heritage, and then without any feeling of strangeness add dramatic orchestral strings to complete the mood, and have a finale based on a qawwali. Bollywood music is constantly learning, incorporating Hollywood conventions in the 1940s and 1950s, and then updating its music according to the changing conventions and tastes. Electronic production and rap were easily and swiftly incorporated into the Bollywood tradition without displacing any of the traditional instruments or overwhelming the subtle artistry of the singers.

This flexibility benefits the backing score as well as the songs. The extreme beauty of solo Hindustani instruments can feature in emotional interludes, while more traditional western scoring can be used for drama. Music directors seem to regard their different genres and traditions as part of a palette rather than a defining format, with many expressing the opinion that it is better to use the emotional dynamism of Western music for sad or tense moments, and leaving Indian music to either happier moments or the songs themselves.

Freer music makes for better songs in both the context of the film and beyond it. Lyricist is a role separate from the music director or scriptwriter, and it is a generic convention that the words of songs will be in a higher poetic register than the main dialogue. These different ranges help Bollywood appeal to the full spectrum of Indian demographics, a requirement for financial success, but also make for incredibly versatile films. In Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham (2001), Kareena Kapoor plays an outrageous comic relief character throughout most of the film, only towards the end working as a helper in the film’s central family reconciliation plot. But that character transformation is nowhere better exemplified in her central song “Bole Chudiyan.” Her flirtation with Hrithik Roshan’s character turns into a celebration of family set during the festival of Karva Chauth, and the song manages to accomplish in one blow the transition from her plot line into the final act focused on others. This process of youthful romance turned into an affirmation of the family makes this a perfect wedding song which is exactly what it has become, with many who knew the film and many who don’t dancing to it on memorable nights in their lives. Throughout India and the diaspora, the song has escaped and perfected the film.

—

America can learn from India. While the current status quo and expectations for musicals require them to hold to certain generic formulae, these can be challenged. At present, inserting a sitar or tabla into an American film or stage musical would seem like an out-of-place oriental addition, but through exposure this can change. There are plenty of musical directors, playback singers, and performers who could be enticed to spend time in Hollywood and Broadway thanks to our generous budgets, and this is exactly what the entertainment industry should do. Better music benefits everyone.

I refer throughout this piece to “India” as the site of the musical and film culture I am discussing after considering alternatives. Bollywood is not the film industry of all of India, and is really the Hindi language film industry centered in Mumbai. Many of South Asia’s other film industries follow similar conventions especially in music, and certainly deserve creative credit although I do not discuss them. The theatrical traditions and musical traditions that form the lineage that Bollywood draws from are broadly South Asian, and notably Qawwali is part of the continent’s Muslim heritage, and the Parsi theater conducted largely in Urdu.