Why Did Marxism Succeed?

Resending without an annoying formatting error.

This post tackles a subject which would be better handled in a well-researched book. This is not a book, nor is it particularly well-researched; it is more a hypothesis than a well-synthesized conclusion. The influence of Marxism and the neatness of the historical causation are both exaggerated. However, I want to offer it as an essay because it is my current hypothesis on what has happened to radical political ideology, and what ought to change for the 21st century.

For millennia, the human political imagination had been restricted to monarchy and various forms of local rule by powerful men who are succeeded by their sons. Aristotle had added a few forms of government, little practiced, and there were some variations like the early caliphal system, but monarchy was the lot of the ruled. This changed.

European print culture in the age of revolution saw not only new forms of government, but new theories. At the same time as the English overthrew their king to commence what was either the rule of parliament or a puritan theocracy, a small community of Diggers experimented with religious common ownership of the means of production. The 18th century saw the revival of Roman style mixed democracy, social contract theory, new theories about nationality and natural law, and ended with the wild and bloody implementation of Robespierre’s secular Republic of Virtue. The 19th century went even further, the rise of egalitarian socialism birthing even more ambitious projects which attracted real dedicated partisans: Fourierism, many breeds of socialism, anarchism, syndicalism, Georgism, Zionism, and Marxism. Amid this various sorts of nationalism began a slow conquest of the world.

As the old orders were overturned with WWI and the economic possibilities of man accelerated further, one would expect the 20th century to have even more of these ideologies, and for them to succeed. But this was not the case. Russia and China had incredible revolutions and implemented Marxism, bringing the rest of the 2nd world along with them. America and Western Europe all settled on some variety of democracy modeled on the revolutions of the 18th century. The one truly new live ideology was Fascism, hardly an exciting addition to the possibilities of man’s self-governance. Much of the other invented political philosophies - situationism, or eco-egalitarian movements - are more ethics of disempowered activism rather than mass politics for a future world. The revolutions in the formerly colonized lands of Africa, Asia, and South America mostly stayed within the bounds of the currently practiced ideologies, the defining claim of a third-world leader being that they were between Communism and Capitalism without ever propounding anything substantially new.

In the 21st century, the Marxist governments have largely failed and we have inherited a broad consensus that 18th century political philosophy was largely the end of history. There are a few monarchist and theocratic dissenters, and China, which belongs in a category of its own for its importance, but the conversation is over. And in many of these countries universities are filled with academics whose writing informs youth movements with radical ideas about transforming the world into a better place. And many of these academics are Marxists, either identifying explicitly as such, or drawing explicitly on Marxist ideas without repudiating them.

What is strange about this is not that Marxism is so influential despite its actual incarnations failing (Orthodox Marxists are absolutely correct to point out that Lenin, Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot implemented quite different things from what both Marx wrote and they now preach), but that there are not other completely independent ideologies competing with them. Within the sphere of radical intellectual ideologies, Marxism has succeeded to the point of extinguishing all competition, and within the sphere of practical politics, democratic capitalism has done the same. Change no longer looks possible.

—

Political movements often arise spontaneously, but it is ideologies constructed by individuals that give them shape. Popular peasant rebellions had the intention of establishing new rulers with lower taxation, but the radical change of the French revolution - secularism, self-government, and the abolition of the estates - came through the ideas of its Enlightenment educated leaders.

The authors of political theory in its past golden age follow a pattern. In the 17th and 18th centuries, political theorists were independently wealthy highly educated intellectuals who only very rarely participated in direct political action themselves. Locke, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and Voltaire’s ideas were all carried into revolutionary wars, but none went to war themselves. But their followers who put things into practice, Franklin, Jefferson, Lafayette, and Robespierre came from similar academic backgrounds. A gentleman involved in radical politics often came up with his own theories. Francisco Suarez and Simon Bolivar were voluminous readers and writers. It is notable that perhaps the most radical early revolution, that of Haiti, was the least theorized. Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, born slaves, kept from education, advanced through military and political talent in the unexpected revolution and abolished slavery but did not write about it, falling into a standard imperial system after expelling the French.

In the 19th century, radical politics became accessible and interesting to intellectual circles across the European world, now including the rising and industrialized middle classes. Fourier and Proudhon were both failed businessmen who found patronage in writing about utopian socialism. Towards the 1840s, the radicals tend to be university educated. The young Hegelians came onto the scene and to engage with them it became a prerequisite to be able to understand the intricate complexities of contemporary philosophy, but this was still an open field. In the radical circles of Dostoevsky and Turgenev in 1840’s St. Petersburg, everyone was reading the latest thinking from the continent and debating the correct course for Russia’s transformation. One could be like Valerian Maikov, torn between literature and political economy as two live options for a career.

While some of the post-Hegelian radicals were professors, many were not. Metternich’s continent-wide censorship made it hard to discuss radical politics from a teaching post, so radical graduates had to make their way through other trades and publish in more clandestine ways. Marx, Engels, and Mikhail Bakunin followed this same course, and the First International was largely made up of such educated thinkers employed in something other than academia. The Russian radicals of the 1870s, 80s, and 90s have this same profile: drawing their inspiration from intellectual writing and education but making their own way as revolutionaries. Henry George and Eugene V. Debs did not necessarily draw from particularly complex sources, but did make their own theories and were widely influential. George is maybe the most popular economist ever but had no credentials or training in the subject.

At the dawn of the 20th century, radicals were still small, but their threat was felt. Amid high profile anarchist assassinations and rising popular socialist movements, the strange overeducated writers and thinkers of the 19th century seemed to have been the architects of the next age of mankind. Marx’s legacy was still only minor, having won factional fights in Russia but little else, and it would be reasonable to believe that the future was socialist, but not Marxist. The 1905 revolution in Russia featured Marxists among other socialists, but was not a Marxist revolution. The 1917 Revolution was not initially Marxist, but once the Bolsheviks seized power the world of radicals changed.

—

Marx was a profound thinker within the tradition of Western philosophy, creating a subtle system of thought which could explain and accommodate a changing human condition. His ideas directly follow from the philosophy of Hegel, the most prominent and influential philosopher of the first half of the 19th century, whose ideas were also famously obtuse. Hegel wove a complicated philosophy of perception and reality and most importantly for Marx, gave it a historical scheme. He was a rather boring lifelong Prussian and noticed that the history of philosophy progressed at about the same pace as the politics of the Prussian state (at least over the previous two hundred years). From this and many abstract metaphysical considerations he concluded that the overall spirit of humanity and of reality was converging in his own Philosophy and his own Prussian government.

This was clearly false and Marx was just one of many, many students to rebel against it. Marx the political exile saw where true progress was heading in the factories of England. At Hegel’s death, Prussia had essentially completed its political modernization process but had not yet begun the far more massive transformation with industrialization. Marx and his collaborator Engels’s direct observation of the factories led them to believe that Hegel had been right about the progress of the West, but that the progress had not finished.

But what Hegel had given to Marx was a way to fuse complicated technical philosophy with a teleological progression of history. The idea of history culminating in an ultimate good state came not so secretly from Christian metaphysics, but Hegel was able to repackage it in a secular garb. Marx repudiated Christianity and his worldview was fully atheist, but his philosophy retains this ultimate trust in historical progress.

Historical teleology also crucially allowed Marx to sidestep the question of ethics. If communism resolves all the spiritual issues of man and is the definitive and inevitable end of history, ethics in our fallen times don’t truly matter. Marxism as a system predicts that this revolution will take place, but does not proscribe action one way or another. Marx and Marx’s followers plainly believed that working to achieve the final state of global communism was moral, and the language used to describe capitalist alienation makes it clear it is not a good or preferable state, but he never feels the need to make a formal moral argument similar to what Utilitarians or Kantians would propose.

But Marx also reversed many elements of Hegel’s philosophy. Hegel’s view of reality emphasized ideas, philosophy, and spirit, whereas Marx’s doctrines emphasized materialism, economics, and the practical. Marx’s later work sees the empirical-theoretical discipline of economics, justified in the empirical data of history, as a key source of his overall philosophy. Using the economic paradigms of the mid-19th century, Marx shows that capitalism will necessarily and inevitably lead to fundamental conflict between a narrow group of owners and an increasingly large and exploited proletariat. This economic principle is what would lead to the final communist revolution.

—

Marxism is quite complicated. Spread across several massive, difficult, and dry books, it requires serious effort to understand, and it is no wonder that very few people read them in the author’s lifetime. His books were so boring that the Russian censors did not bother to read them and allowed them to be published. Some educated Russian socialists who had been active for decades read these, but most took little notice except for a small group of very intellectual but initially not very influential journalists which included the young Lenin.

Historical causality is extremely difficult to define or establish, but it would be very hard to argue that Marxism was a primary cause of the Russian revolution. Nearly all of the Russian radicals who joined the early Marxists were already committed socialists long before they encountered his ideas. But Lenin and his colleagues found Marx’s economic theories and predictions convincing and were themselves extremely effective at winning inter-party power struggles (it is possible that Marx’s complexity aided with this), thus making the Marxists into an extremely powerful faction leading into the 1917 revolution. That Marx himself had no confidence in Russia as a potential location for communist victory did not discourage them, and the Bolshevik party seized power in the dramatic takeover of November 1917.

Marxism was the first revolutionary socialist philosophy to actually take over a government and to last. The Soviet Union was a major world power, and the Bolshevik’s success only became clearer during the following civil wars and period of consolidation. This success, and the Soviet Union’s extensive international networks, rallied radical movements throughout the world and many who would never have otherwise heard of Marx themselves became Marxists. The Soviet Union’s success, and the subsequent success of Tito, Mao, Castro, and Ho Chi Minh, was a key reason why Marxism came to dominate in leftist circles.

While governments sought to suppress Marxism, they rarely did so by encouraging other forms of socialism, and in the face of state repression leftists either recanted the whole project or joined the Marxist underground. In the United States for example, a lively socialist movement of the early 20th century was effectively driven into extinction thanks to the efforts of the government and popular press. Georgism and the socialism of Eugene V. Debs were abandoned as politically and intellectually toxic. Reformers joined the New Deal project of Roosevelt, but for the narrow few who rejected compromise and still wanted a fundamental change, Marxism became the only live option. For aspiring radicals, Marxism had the radical appeal of the forbidden, and was able to survive and spread in these difficult times.

These reasons above explain why Marxism became the most powerful force in radical leftist politics, but they do not explain why Marxism became the only one. In the relatively free intellectual environment of the post-war United States and Western Europe, as well as India, Japan, and South and Central America, there were plenty of opportunities for other theories to emerge and contend for preeminence, but they did not, largely getting beaten out by Marxism. Intellectuals love to make their own theories that overthrow all past knowledge as the unique solution to man’s age old problems, so it is surprising that in the field of politics this largely did not happen. Philosophers like Derrida and Badiou asserted that they were overturning the entire tradition of Western knowledge and Philosophy, but where asked to weigh in on politics, they largely made it clear that they were not seriously challenging Marxism. In the hybrid domain that Marx had claimed, the academy had nothing new to offer.

—

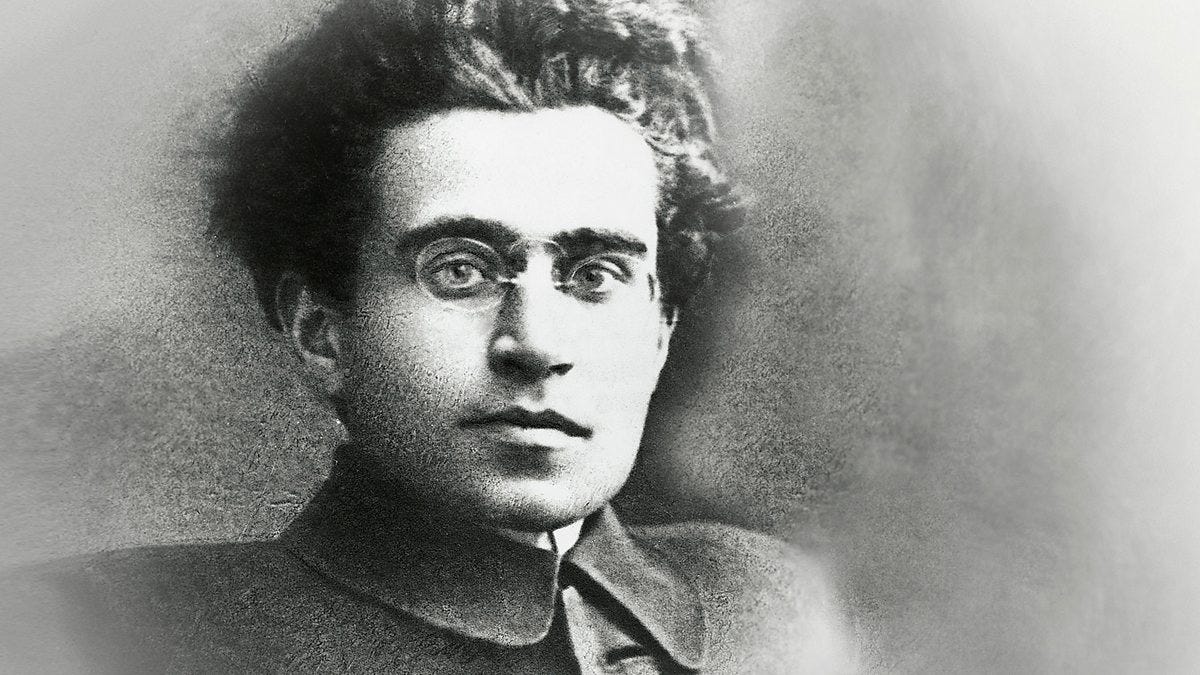

Of the major political intellectuals, the 19th century saw the end of those, like Marx, who attended university and then left to theorize outside of the academy. The generation of the gentleman-theorist-revolutionary was over, and theorists of all ideologies became professors exclusively. Within the Marxist tradition itself there is a bifurcation between major figures: the intellectuals and the revolutionaries. Gramsci and Trotsky were probably the last of the true intellectual-revolutionary fusion that many seem to idealize, and those that came after belong to one side or the other. Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Althusser were all professors and have left important theoretical contributions to Marxism as it is now. Stalin, Mao, and Che owe their influence to their political success, and are in a very different mold.

For those safely in the ivory tower who were committed to radical politics and to the moral cause of justice for the oppressed Marxism was attractive - it was complex philosophy about politics - but also offered crucial tools useful for realizing academic incentives. In intellectual competition between professors Marxism was uniquely equipped for victory. As a fusion of metaphysics, history, economics, and politics, Marxism allowed its adherents to use any of these fields against opponents who did only one. Pure philosophers were insufficiently historical or economic, whereas political scientists could be critiqued for their lack of attention to historical economics, and economists could be defeated with philosophy that they failed to understand. And if one did not have access to a graduate-level education, one was hopeless against a well-trained Marxist. Marx was a brilliant thinker and a brilliant critic, but also significantly benefitted from the 19th century environment in which it was possible to know all of these fields to a reasonable degree at once. By the early 20th century, academic specialization had advanced to the point where the number of people who had a solid grip on Hegelian metaphysics, world history, and the latest theories of economics were extremely slim.

Marxism’s academic victories were not evenly distributed though. It succeeded most in the fields closest to pure theory, where the moral-political bent alone could displace opponents. Economists had the strongest internal belief that their field was an independent empirical science, and were happy simply to ignore the claims that they were immoral or unphilosophical. Marx’s economic claims insofar as they were empirically falsifiable have mostly been falsified, and the remaining Marxist economists are Marxist out of political-moral conviction rather than out of empirical or theoretical developments.

This divergence has only widened over time and has variously contributed to cultural struggles such as the science wars of the 1990s. Most Marxists come from the theoretical disciplines and have little training in economics, but Marxism allows them to claim that their economist opponents have gotten economics wrong through inattention to their own specialized disciplines. Sometimes they go further and claim that non-Marxist capitalist economics has triumphed not because it is true or correct, but because it is favored by the powers that be, or even encouraged by such entities as security forces, a theory that is unfortunately at least partially true.

Another important element of Marxism’s success is its potential for minimal commitments. Marx’s theories contain a number of beliefs and practices including but not limited to: a belief in Marx’s particular teleology of history, belief in worker’s communism as a final state of history, belief in the empirical validity of Marx’s economic work, belief in the idea that capitalism is fundamentally alienating, commitment to class struggle as a way to advance history, opposition to a hegemonic capitalist ideology, belief in a materialist model of history, etc. Almost no Marxists are fully orthodox, but such a wide variety of potential entrances allows for the formation of a Marxist orthodoxy in academia. There are plenty of scholars who identify as Marxist simply because they support the advancement of the poor in a revolutionary rather than incremental way, or who do so because it is the orthodoxy of their field and there is no need to pick a fight over such a minimal expression of solidarity or obedience. Besides, the best way to publish is to make your claims as minimal as possible. Philosophers are supposed to be cited, not exceeded.

All these factors have created the great Marxist consensus across the humanities. Capitalism is fundamentally alienating, immoral, and oppressive, only drastic revolutionary change can fix it, and this teleological endpoint is best advanced by writing more papers on the theory of art, gender, cinema, literature, philosophy, or anthropology. It is an odd conclusion, and not usually asserted explicitly, but it is the conclusion which has been reached by thousands of practicing scholars. For anyone who dissents, the incredible discursive tools of Marxism can be used against them, and anyone outside academia can be safely disposed of using the same methodology.

—

Marxism has waned in the last few decades. While academics maintain the same commitments - suspicion of capitalism, radical transformation of society, etc - they have identified less explicitly with Marxism, preferring a more generalized and vague identification with leftism as a whole. Identitarian views of history and progress derived implicitly from Marxist teleology have become a background belief in parts of academia. The utopia imagined as the endpoint of racial justice or climate justice or intersectional justice is the same Marxist culmination as previous generations, but at this point it has become so vague that it has no particular qualities, nor any real arguments about its nature.

While explicit reference to Marxist or Hegelian logic has faded, the same moves of Marxist academic arguments have persisted. Other theories are insufficient because they fail to take into account the history of racism of an idea, or the lived experience of a forgotten community ignored by capitalism. Every discipline can be attacked from every other discipline, and attempts at true synthesis are dismissed. While the Marxists excelled at this form of competition during their academic height, this kind of competition and battle is ultimately created by the structures of the university itself. In this environment, theories will defeat theories according to which is better armed, and Marxism is slowly being eaten by its children.

Orthodox Marxists are fighting a losing battle. They have critiqued the recent transitions in the academy away from economic fundamentalism, arguing that radical politics is betrayed if it just becomes a relativist competition between educated elites, and they are absolutely correct. But they are dismissed as a fading old guard compared to the new horizons of pure and unpractical theory. The inter-elite competition within the ivory tower has only gotten worse, and has spread from the academy into many parts of our increasingly overeducated society. Nonprofits, political organizations, and cultural institutions have all been overwhelmed, and paralyzed. A philosophy which was originally supposed to be the beginning of ideas that change the world are at risk of keeping it the same. Hegel may have defeated his old student in the long run.

—

Marxism is not advancing. While theorists have proposed an idea of “Late Capitalism” which shows that the changes of the last decades are really all compatible with some sort of coming Marxian revolution, these are the whimpers of a fading paradigm. The proletariat are not becoming more impoverished, nor are they even growing. The mass industrialization that Marx saw as the engine of the last stages of history has spread through the world, and more and more of humanity are finding themselves happy with its banal but substantive products. We are far from any final state of existence or society and there is plenty of alienation, but Marxism’s tools rarely clarify what is or what is to be done beyond a simple rejection of the status quo. In this it has become a rather unreflective orthodoxy.

Economics, the science that Marx believed in most, has advanced substantially, but has settled into something of an orthodoxy as well. Economic organs and governments seem essentially content to propagate current relationships and industries with their primary goal being a lack of disruption for the status quo. Those who have the most effect on how the world develops are competent bureaucrats dealing with great unknowns they are steering around.

There has been enough observation of the world as it is, the task now is to change it. Marxism should be discarded as an influential 19th century theory, and young radicals should aim to start things anew and surpass Marx. Philosophy, politics, and economics should be ripped from the confines of the academy and be debated and experimented on as live projects. We should return to the time when poets and journalists could be making their own theories of economics, because one of them may end up being right. Henry George’s policy proposals were chased out of respectable discussion in favor of more academic theory, but now the land-value tax has a much greater chance of changing the 21st century than any ideas of George’s detractors from the left or right. New ideas are extremely valuable, and it is an incredible failure of civilization that we have stopped producing them.

As long as arguments about politics and economics remain purely theoretical, this will not change. As long as people who want to advance the world are vulnerable to being shut down by someone with more specialized academic knowledge, this will not change. We need new ideas, and we need to act on them.