What does it look like to make a moral decision?

Pacing back and forth, scratching one’s chin, intense discussions with a sequence of friends and advisors, pro and con lists, imagining possible outcomes in the shower - these are all potential parts of a process of grave importance but no formal structure. Most moral decisions are made with little forethought as part of daily life, the product of habit or whim more than careful consideration, but even when we recognize that an upcoming decision will be important we have very little in terms of explicit frameworks about the best method of making such a decision.

Practical reasoning is extremely difficult, and most attempts to formalize it have largely stayed in the realm of the theoretical because any implementation is woefully inadequate compared to what we demand of our own idiosyncratic practices. But this hides the fact that the current standard is also inadequate. I have changed my mind on decisions big and small after conversations with friends, but which friends I talk to is often determined by coincidences such as where people are and if they’re free. Sometimes I change my mind based on reading something particularly relevant which was coincidently found in a book I read for other reasons.

Even more inadequate is that there is very little discussion in our culture of how one ought to make important decisions. It is left for every individual to figure out by themselves and for no one to question. Friends are only ever advisors, never correctors, family are meddlers if they overstep a distanced role. “Sleep on it,” “try writing about it,” “talk to your mother” are all largely good pieces of advice, but they are the vague folk remedies of morality. It may take a while to get to medicine, but it’s worth trying for.

—

Most deliberation occurs through language, whether it is dialogue or internal reflection. The recent technological breakthrough in Large Language Models (LLMs) offers the opportunity to make systems for moral reflection that enhance some of the above methods, primarily writing about situations or attempting to understand them better through devices like pro-and-con lists.

Imagine you are attempting to make a difficult decision: you have a finite guest list for a wedding and need to decide whether to invite a somewhat close friend or a somewhat distant aunt. You might begin writing about the situation, describing the situation of each and your relationship with them. This is what you feel the issue is, and your resentment towards the familial responsibility exerted by your father is coloring your emotions. A properly trained systems might ask questions.

“Who would they sit with?”

Not a hard question or a useful one, the aunt would sit with the family, the friends with the friends.

“Who would enjoy it more?”

This may be more interesting, an angle you haven’t considered. You will be busy, you won’t have a huge amount of time to talk with either, and the friend doesn’t actually know the other invited friends very well.

Questions might continue in this way. You might still choose to invite the friend. But maybe the system led you to think more carefully than you otherwise would have.

—

There are a lot of potential functions for such a system using existing or soon-to-exist technology. You might have an LLM help imagine divergent scenarios that would come about from your actions. You might have it pull in relevant factual information (does giving cash to beggars who are drug addicts actually hurt them) or relate it to some other source you respect (there is an analogous social situation in a novel you have not yet read but whose author you respect). Ideas like a moral parliament, different ethical theories each represented by a different agent capable of voting and possibly discussing, could be realized in miniature. Moral tools have a lot of potential for creativity.

I do not have the capacity to dictate the correct process for moral deliberation, nor would I trust others who wanted that power, so this system should ideally be a tool for better refining the values of the individual user or independent communities. This is not a tool where moral principles are handed down from above by a trusted AI, but a cyborgian system which enhances human consciousness. Users would have full access to how the system works, modify it themselves, and create their own structures. I would hope that over time communities of moral practice would develop and the tool would be a gateway towards greater explicit discussion of how one ought to decide and to live. People could share particular modules and techniques, and through that come closer to shared correct moral values. But we can’t move too fast, healthcare went through many phases of bad top-down interventions before it broke through to truly helping patients.

—

There are many risks. As with any widely distributed technology, mistakes that are normally individual might become systematic. LLMs are extremely complicated and widely misunderstood already, and influencing many people’s moral behaviors simultaneously could create bad outcomes. Factual pulls may be inappropriately scrutinized or there may be biases for or against certain principles. There is also the possibility that certain kinds of moral deliberation might be harder for AIs to contribute to, leading to a situation where they are undervalued. Many advocate for making decisions based on barely-verbal gut instincts, and increasing deliberation might muddy one’s more valid first impulse.

Ideally the user of such a system will keep its conclusions at arms length. They will understand how it influences them, and ensure that it only influences them towards doing better. If the AI suggests something slightly more moral, then the user will follow that advice, if it suggests something worse, it will be discarded. The system would be designed to encourage such attitudes. But this perhaps puts too much trust in the users. The greatest danger is that access to a moral AI system will allow for a culpability-dodging appeal to authority on all major choices. Especially in current Western culture which has given so much authority over knowledge to science and technology, people like to hear that their decisions are approved by some furmula and like to not have to make difficult choices. But this danger may come from other directions as well.

—

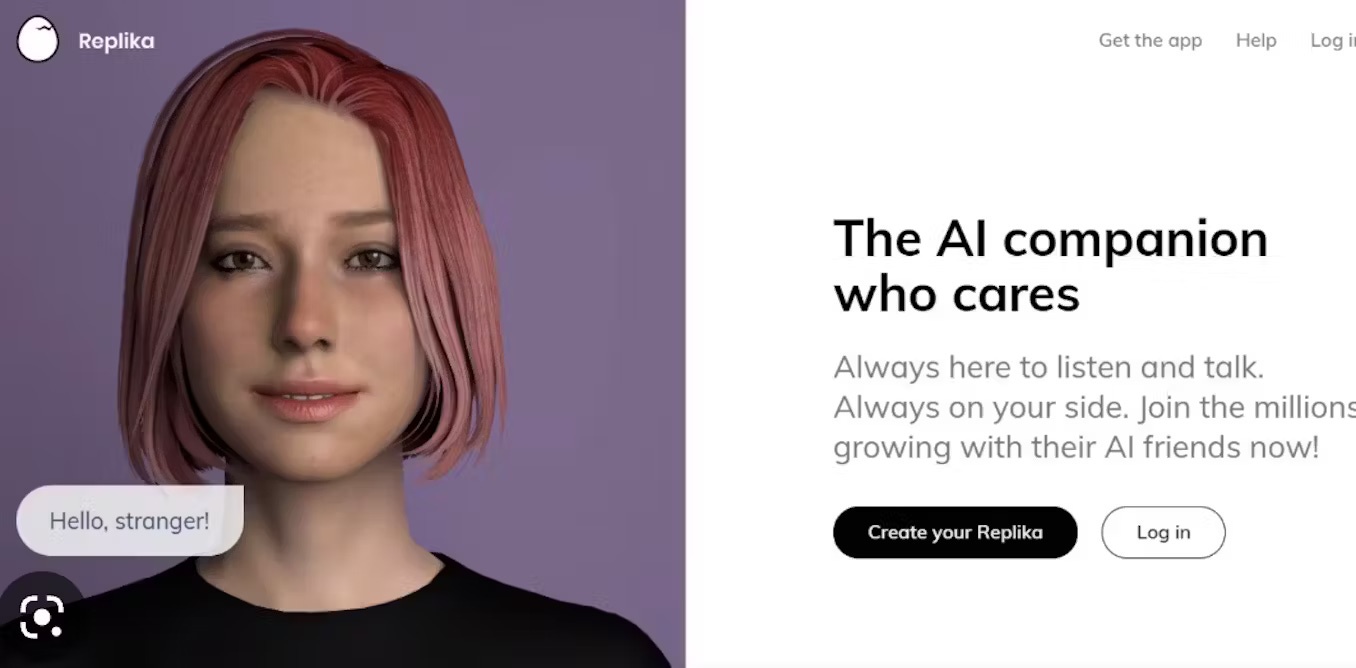

There is an alternative to a cyborgian tool for moral deliberation. The personal conversational AI which knows all about your life, talks through all your issues with you, and provides (corporate-sponsor approved) advice on whatever you ask it. An AI that you grow up with and trust and use for all your tasks is at this point inevitable. The idea has been had by thousands of ambitious companies and founders, and is surely being developed, and it will hit the market as soon as the technology is mature enough.

All of the above risks apply to such a system, but may be worse. While some companies might shrink from the potential liability of advising decisions with “As an AI I cannot give advice on…”, the human demand for the comfort of authority will eventually triumph. People will want to make decisions because their AI told them to, and their AI will tell them even if the decisions aren’t good.

Such AI systems pose a serious risk of moral lock-in. Communities will enact whatever moral values their AI instills in them, and the AI’s values will be determined based on the logic of product and not on truth. Currently the most likely candidate for a global moral system instituted through AI is generic individualistic liberalism which is far from the worst system, but is obviously not the final ethical truth we ought to strive for. But there are far worse systems, and probably far worse effects even from a seemingly harmless system, and we should worry about them.

The tool I have described above which preserves individual and collective user inquiry will have to compete against the top-down system. It may be that letting people decide for themselves rather than letting companies bound by a polite consensus leads to worse outcomes. But my hope is that at the very least, some components and spirit of the more open system will at least make the top-down system a little more moral.

—

These systems are possible with current technology, but require some work to implement. It is worth starting now, starting with the basics, with small improvements.

Most moral decisions are habitual, but might change with deliberation. Until recently, I did not ever give money to beggars, believing that extra cash likely hurt them more than it helped. Without intending to investigate this question, some reading of unrelated articles and some discussions with trusted friends led me to changing my mind. I’m still forming the new habit of giving, and haven’t yet been good about keeping small bills handy, but I am improving. Many of our moral practices may be based on unexamined truisms, and I hope that the project of making deliberation more explicit itself is an opportunity to do a little more good, even if the tech fails or the advice given offers no improvements itself.

If you are interested in discussing more about this project or have ideas I may not have considered, please get in contact at ethanmedwards at gmail dot com.