Reading in other words

Modernity is partially defined by the standard of writing in the native vernacular. In this era writers who have adopted a learned language as their medium can be easily clustered by this peculiarity - Joseph Conrad and Samuel Beckett are joined by Vladimir Nabokov until it is explained that the last spoke English as his first language in a privileged Russian childhood. Conrad, like many others on the extended list such as Agota Kristof or Ha Jin, wrote in the language of his adopted homeland when return was not practical, and economic incentives were no doubt in play. Beckett chose French for more obscure aesthetic reasons, to write without style. The latest name to join their rank is Jhumpa Lahiri, an American writer well established in the current literary world, who has chosen to write in Italian, and has written about her relationship to that language in her book In altre parole.

Lahiri, in a style sparsely decorated with sequences of simple nouns and adjectives, writes about the process of learning this language, living it, and writing in it. I read the work in its original Italian without having studied the language beforehand, using a specialized interlinear translation with explanation I made for this purpose. I have reading knowledge of French and Latin, and have at times tackled bits of Spanish and Portuguese, and had once or twice skimmed a grammar of Italian before a trip to figure out what “gli” means, so the forms were already familiar to me. To read this book while learning Italian offers a unique joy of having the reading process itself described in carefully layered metaphors.

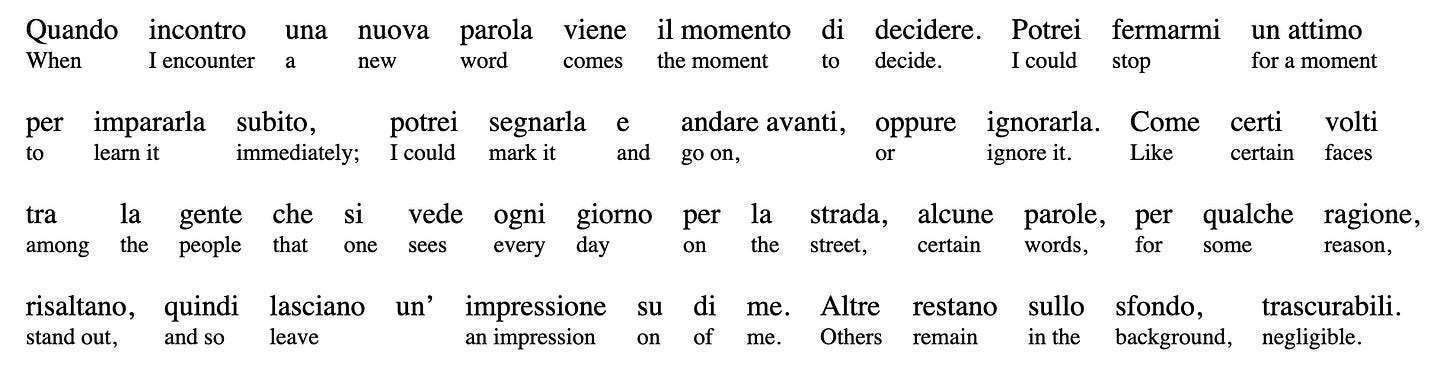

It was a process of discovery. Each paragraph was a new territory which I understood through matching the words I had just seen and guessing at the new ones. Every word remembered or phrase understood without reference gives a smile of progress. And the moments when one truly swims without aid, even for a moment, feel magical. Metaphors of movement - travel and navigation - dominate the book and the process. Words are landmarks. As Lahiri describes her early reading:

Lahiri was reading Italian using one of her many paper dictionaries, so this moment of decision is a crossroads between the flow of reading, and an interruption. Sorting alphabetic sequences means totally losing the sentence one has stumbled in the middle of. To press on, placing motion over knowledge, has a thrill to it, but one can get lost. This how reading has usually worked for the learner.

My tool reduces this friction, looking up the word is just the decision to reveal it, and one rarely gets lost for long. But this decision matters for the experience. To see every word in English is to surrender any chance it has to leave an impression, and to make all of Italian trascurabili, the read text becomes just a garbled translation. The decision to test limits, to play actively with one’s own understanding of the language, opens a kind of reading accessible only to the learner, delighting in failures and finding.

At times when stumbling through difficult paragraphs in a language I have no strong attraction to, I wondered if this adventure was all a mistake. The book has been published first in Italian, then soon after in English. The person responsible for the latter, Ann Goldstein, is currently the most famous translator of Italian, having brought Elena Ferrante to the Anglophone world with some saying that this most famous living Italian writer’s reputation, greater in America and England than Italy, probably owes quite a lot to her translator’s style. Goldstein has a quiet claim to perhaps being a better writer than the best Italian, so avoiding her English should hardly be a priority. Reading Italian, I am proud of every sentence I comprehend, and especially every literary nuance I grasp, but I am missing far more, and what I am missing is certainly grasped by Goldstein and rendered into English in a way that I would understand fluently. By choosing to read in a language I barely know, I am very likely losing many of the nuances of style which is for many the reason to read literature, and is certainly the reason to read in the original.

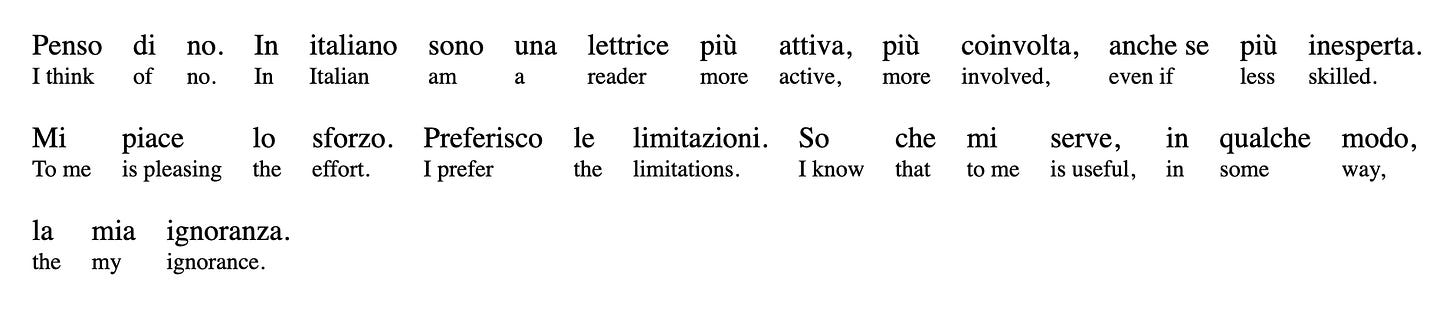

This fundamental limitation of a second language is what Lahiri feels the need to address most directly, for it applies to her as a reader and even moreso after she makes the decision to write in the new language.

She ultimately identifies herself with these limitazioni, the foreignness at the heart of identity which runs through all her literary work. But that is much more lofty and personal, more basic to my task is whether reading più activa and più coinvolta is better. Looking back and forth between words, tracing the semantic flow of every clause, is a kind of reading that typically happens only in two contexts - language learning and exegesis. The constant transit between reference and original is the key here, always searching, imperfectly, to grasp the full meaning. I would have enjoyed the Goldstein translation, but every turn of phrase I particularly appreciated would contain with it the question “how was this in the original?” In normal reading, I would press on without bothering to answer such questions because the process of checking would be far too involved, and the luxury of the fluent reader is that I don’t need to answer such questions. Exegesis requires one to go over every angle of a word and its neighbors, questions cannot be put aside without changing the nature of the reading. Language learning requires this same attitude, because even the basic grasping of meaning would be impossible without it. That Lahiri desires this slower reading, cross checking for each resonant word’s equivalent, is not only evident from her description of it, but the fact that the Goldstein translation has only been published in a facing page edition alongside Lahiri’s original.

Fluency allows the language to wash over one, picking up the beauty of the shapes and inventions in real time, but it allows us also to read too fast. I recently listened to the RTÉ Radio broadcast of Ulysses which was magnificent and entertaining, but my appreciation of the novel remains joyfully partial. Even at my 2nd time through the novel, I understood less than I did of Lahiri’s Italian. The pleasure of the glimpses I had though inspire me to complement this experience with a proper exegesis, which means reading, rereading when I stumble, and in this case consulting extensive commentaries as well. I am thankful that I do not need to learn English in order to read Ulysses, but there is another sense in which that’s exactly what I need to do. Slow and deliberate reading, the kind that loves language and wants to explore its manifolds, is so similar to language learning that they naturally flow together. Translations can stand on their own, sometimes they are better than the original, sometimes they are for a simple skim which can still carry much of the weight of the original’s meaning and aesthetic. But many translations also know their devoted readers will have these questions and can’t simply ignore them. Devoted readers of Kafka at least know Ungeziefer, Homer is about nostos. The desire for the original is there. Footnotes are halfway there.

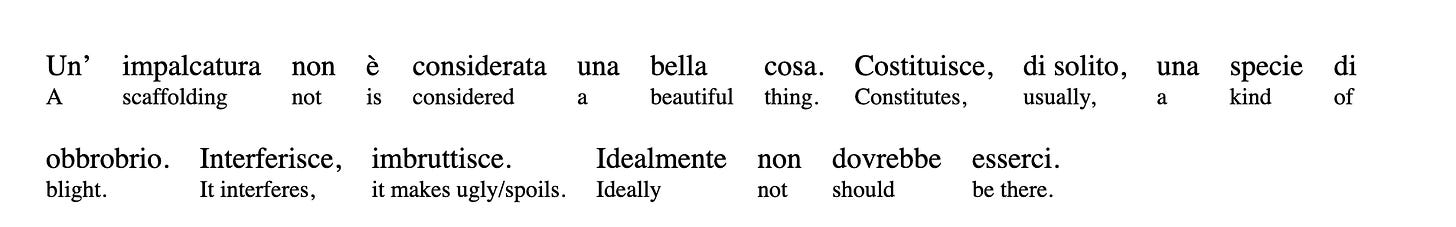

As Lahiri reflects at the end on her uncertain triumph of publishing In altre parole, and making the commitment to abandon her mother tongue to write in an acquired second language, she details her dependence in this foreign territory. Her teachers, readers, editors, and publishers have all put the book through many phases of refinement, the sort of extra care that only native speakers possess. They are performing parts of the task of writing, of actually choosing the words that readers will encounter. As a solitary artist, the writer really isn’t supposed to do this, certainly not to confess to it. Editors are supposed to make suggestions, not hold up the art themselves. It troubles Lahiri, but not too much.

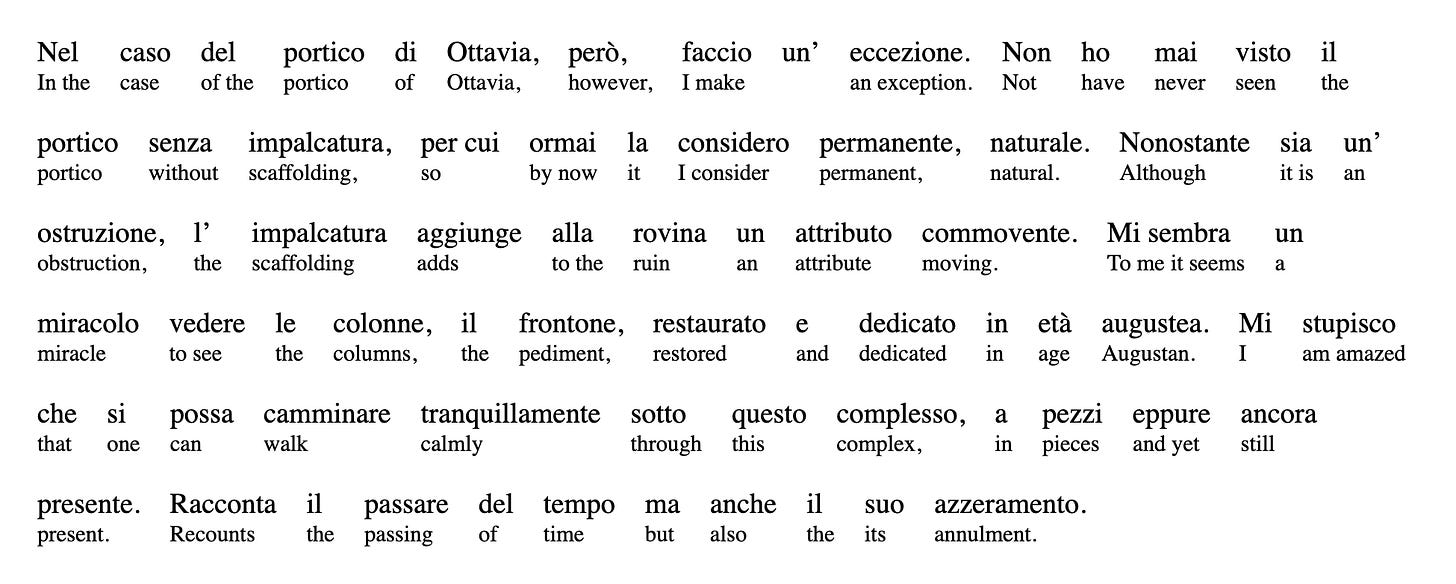

Impalcatura is always a limitazione. One avoids going to a great site while it is up, preventing the view of the original. But so much of beauty is in that more labored peering which not only removes the scaffolding, but can go back to the original and appreciate the feeling of the ruin that has only traces of the original.

Poets have fought across the millennia over whether the splendor of a triumph is more fitting for art than ruins or memory. The essence of the cherry blossoms might be their inevitable falling and fading, or it might just be their obvious splendid colors. One is free to choose natural fluency as the only true path to art. But scaffolding has enough claims to be worth building. Ruined buildings and dead languages have no chance at their original immediacy, and rarely were meant to. Simply translating them into the present is an act of respect, but incomplete.

Lahiri is throughout conscious of being a contemporary writer held to contemporary standards. Writing is about fluent style and an authentic voice presented in the author’s mother tongue in the modern vernacular. Her choice to write in Italian is so obviously in contradiction that she spends the book in a defensive posture, the only arguments are made in terse metaphors grounded in reflections on personal identity, a substance acceptable to these times. She compares herself to the other modern writers who broke this taboo and managed to establish themselves in this modern canon and continues to use their language of exile in a vernacular world. But her success opens some better paths.

There is a pleasing irony to Lahiri establishing herself in the hegemonic common tongue of our time and then choosing, of all languages, to write in Italian, bound to an aging population in a small European country. Before the vernacular, writers felt no need to apologize for using scaffolding, the Chinese poets rummaged through their rhyming dictionaries, good Latin style came from knowing Cicero more than speaking naturally. Part of what changed this was Dante, writing appropriately in Latin and using the language of practiced scholasticism, arguing that there was good reasons to use his native Florentine in poetic composition, and then making the argument more forcefully in the example of the Commedia. Dante’s Florentine absorbed its centuries of august reputation until the distinctly modern tides of nationalism turned it into Italian (and began the eradication of all those smaller dialects which coexisted through the time). Lahiri is defending herself against the contemporary arbiters of fluent style, but the greater ideological conflict is with the father of writing in Italian. She does not make the argument, but she is right.

Writers need not be restricted to the language they know with native fluency. It did not stop any of the great writers of the long past. Lahiri should continue to write in Italian, but more writers should take up English if it suits them, go back to Latin, experiment with constructed languages, take freely all that does not belong to them in the service of art.

The expectation that writers need to speak their language is an artifact of history, an unchallenged assumption of modernity. The expectation that readers will refuse to read anything which requires some extra work, some extra help, is mostly true. But the desire to know is still there. With permission and the right scaffolding, they can get there.

Hearing about Jhumpa Lahiri brings me back to high school when I read The Interpreter of Maladies. Now that I think about it, the titular story may have mentioned translation as well, which may be interesting to look at in the context of this.

This piece has me feeling remotivated to attempt language learning.