Iran has been inhabited for 2,500 years by Iranians with few interruptions, and Iranians prize the continuity of their culture. Their poetry is 1,000 years old, their art even older, and their traditions truly ancient.

Persian classical music is an incredible art form. It is capable of sustained, interesting, and beautiful improvisation for extended times. The twelve modes or dastgah can make enough music for many lifetimes, and have. But how many lifetimes it has lasted already is less clear.

When investigating general sources on Persian music, one finds the claim that, like all of Iranian culture, it is ancient and august. Barbad, the great composer and performer of the court of the last pre-Islamic shah Khosrau II, is said to have invented it. The instruments and the dastgahs are his creation, and his memory is preserved in the written works of his Islamic descendants such as the poet Ferdowsi, whose own words were set to music. The great theorists of the Islamic middle ages such as Ibn Sina and Al-Farabi (both possibly Persian) have sketched the outlines of the perfect interval systems which Persian music realizes. The modern masters, Mohammed-Reza Lotfi and Mohammad-Reza Shajarian, playing with the modes described by the philosophers, singing the words of Ferdowsi and Sa’di, are said to be continuing the tradition that Barbad began.

This history is nice, but hard to trust. Without both written music and careful descriptions of physical sound reproduction, music from before the age of recording is irretrievably lost. To establish that Lotfi playing the Setar is directly descended from Barbad’s performances on his own lute, we would need to either establish exactly the music Barbad played, or trace Barbad’s exact legacy from generation to generation until reaching the safer epistemological realm of recorded music. Both of these are impossible using current historical methods, but the latter is worth exploring, especially in reverse. Where does the music we have now come from, and is a thread that leads back all the way?

Contemporary Persian classical music can be reliably traced back to the beginning of the 20th century through a web of student-teacher relationships. The limited short recordings of the earliest era seem to be excerpting the same fundamental style of performance that is taught today. The main stringed instrumentalists all can trace their lineage back to late Qajar court musician and teacher Mirza Abdollah (1843-1918), and while oral transmission is messy enough that there are many different versions of his teaching the essence is the same between. The singing and Nay repertoires are also continuous with their own Qajar legacies, but see significant influence from Mirza Abdollah’s style. This is a firm starting point.

—

Even the 20th century is not without its deviations. Among the Persian instruments, many of them hundreds or thousands of years old, some have shifted in priority and in style. Within this century, the Setar has gone from being an accessory to the larger and more revered Tar into its own solo instrument. The Tonbak, previously used only for percussion backing, has also become much more versatile, with possible influence from its cousin the Hindustani Tabla thanks to modern recording and radio. Western music has also infiltrated in a variety of ways. Midcentury masters experimented with the Violin and even strangely tuned Pianos. The standardization of Persian music according to theory has also involved an intrusion of Western thought, with some teachers arguing that the sounds outside of the twenty four notes of the harmonic scale are still equal tempered and represent quarter tones, although there is no documentation of equal temperament before direct European influence.

More subtly, amidst the trauma of the Islamic revolution and the changing role of music, changes are still happening. Many of the great masters of today tend to perform less “pure” Persian classical and instead have concerts and recordings centered around the idea of world music. They collaborate with musicians from America, West Africa, and the Middle East, and make incredible skilled music which draws from the Persian canon, but is a distinct genre. When performing for audiences abroad, both Iranian and foreign, there is also a certain pressure to emphasize the Sufi legacy of the music, and to play for the purposes of contemplation and meditation which has real but tenuous links to the older traditions. These come from the pressures of the music industry, from the personal and financial needs of performers, and from the simple entropy that is inherent to all living traditions. Persian music is still Persian music, but given enough time it may drift into something else.

This insistence on tradition and preservation may itself be a 20th century deviation though. The Pahlavi era saw a top-down insistence on the uniqueness, continuity, and antiquity of Iranian culture. The Shah held a 2,500 year anniversary celebration of the founding of the empire and the vast number of Arabic loan words in the language were replaced with Persianate neologisms. Within this political-cultural project, it is not surprising that the uniqueness and continuity of Persian music from the days of Barbad was also insisted on. This hides the alternatives.

—

Whether Persian classical music comes from the roots of the nation or not, it is definitely continuous with the court music of the Qajar Shahs, which Mirza Abdollah was an exemplar of. Mirza Abdollah in his time was known as an excellent teacher and one of the finest players of the Tar and Setar, but he was not the greatest musician. The most honored instrument of the period was the Santur, and its greatest exponent Mohammad Sadeq Khan who carried on a family legacy with the instrument. These musicians would play for the Shah and his various guests in the closing years of the 19th century, making a form of skilled improvisatory music not heard anywhere else in the world. However, Khan and his family made a decision, often the norm for artistic performers in the era, to not teach their techniques to outsiders. Mirza Abdollah was unusual for his interest in education, but it was this decision which caused his style to become the template for all Persian music, while Khan’s died out within decades. Of the greater world of Qajar court music, we have one thread, although a brilliant thread which has been enhanced through generations of master musicians.

Qajar court music itself has uncertain origins. The legacies that informed the late style were certainly in place during the long reign of Naser al-Din Shah, but before that there are just aren’t many good sources to indicate what kind of music was played or listened to. Master musicians do not usually emerge from a vacuum, so it is likely that if they were inventing they were drawing from the previous court music. Perhaps the music of the early Qajar dynasty had the outlines of a modal system and it was the masters of the later era who transformed it into the sophisticated improvisations that we now know.

Before the Qajars was the chaotic 18th century which saw Iran divided between multiple dynasties and civil wars. Amid this turmoil, it is hard to imagine that music was absent, but also hard to imagine that the links of transmission were strong. Musicians may not have had the stable teaching and lifetime of practice to become a Mohammad Sadeq Khan. But perhaps some did. There are speculations that the ascendence of the Qajars came with an infusion of Azeri Turkish culture, including music. It is possible that Persian classic music is not from the lineage of Cyrus at all, but comes from an unbroken line of Turkish clans. But this is not likely either. Before the Qajars, in absence of any solid record of what kind of music was actually played, we can only speculate and look at its fruits.

—

The Medieval and Early Modern world of Iran and its neighbors hosted a common culture with many regional dialects of art, some growing into their own languages. The Safavids and the Ottomans were great rivals, but both honored the Persian past and possibly shared the same musical culture. Musicians are an often itinerant class, and the most skilled could make their way to whatever court was ascendant, whether of a stable imperial dynasty or a more local ruler with wealth to spare. While written sources are sparse, there is not a sense that musical traditions are distinct or separate. Ottoman, Turkish, Arab, or Iranian are descriptions of a musician’s national origin and not their musical style. What for us are genres and sub-genres were in this culture likely considered to be styles associated with a particular style or family. Like Mirza Abdollah, they may have taught or widely, or like Mohammad Sadeq Khan they may have taught only to their own line.

Amid wars and collapses and discontinuities, some of these master musicians likely played for the same court for several generations, perhaps even a century, having enough time to work out the refinements and techniques of an idiosyncratic style. Jazz transformed many times within its first 50 years in the fertile cultural landscape of America, and while the court of a Sultan or Beg may not have offered an equal environment, such variation is possible. Tradition was only what one’s teacher taught, which provided an opportunity for each generation to discover the full possibilities of their idiom.

Exchange certainly happened as well. When the Mughals invaded India, they brought Persian culture with them, and the musicians of this greater continuity. The Setar was transformed into the Sitar, and indigenous styles were transformed into the improvisational Raga system which developed over centuries in the scattered courts of the subcontinent. When 200 years later Nader Shah sacked the Mughal capital, he returned with spoils which included musicians. Persian classical may have created Hindustani music, or Hindustani music may have created Persian classical. Both or neither are possible as well.

Turkish, Arabic, Hindustani, and Persian classical music are all descendants of the many musical styles that were practiced around five hundred years ago. They have certain qualities in common - improvisation, related instruments, a prominent role for soloists and singers - but are each their distinct own traditions which enhance the overall musical landscape of what we have now. They are the descendants that survive, but they may have been many more. Amid all the wealth of the Orient, there were hundreds of courts which could have supported musicians for many hundreds of years. We know nothing about them.

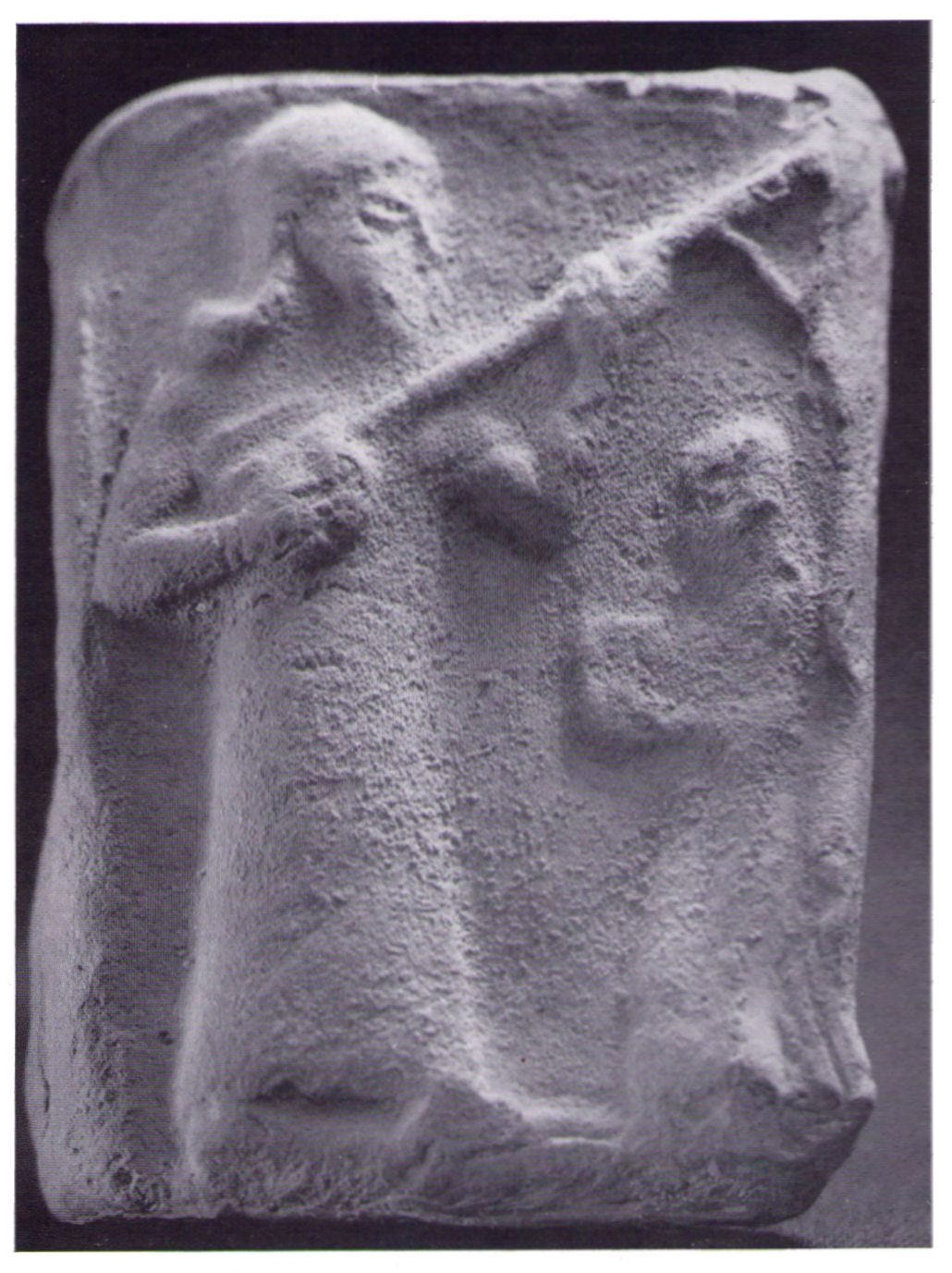

Barbad lived in the splendid court of the Sassanians at the height of their power, and his mastery was spoken of for centuries to follow. But Khosrau was assassinated, Iran descended into civil war, and the Muslims invaded bringing nearly a century of uncertainty following his death. We do not know if any of Barbad’s musical legacy survived at all.

—

Our musical landscape would be richer if we had more of these traditions. But, these traditions formed without consciousness of the alternatives or history, and a more regimented notion of tradition can threaten that. Now that we have recordings of the survivors, the great improvisers should be able to weave them together and make up for what we have lost. Folk histories often posit the creation of a musical repertoire with a few mythical figures - the Carnatic trinity, Gregory the Great, or even Barbad. We have the potential to create such heroes and benefit immensely from them.

But the forces of history may pull in other directions. During times of chaos, improvisatory brilliance may have been reduced to rote repetition of popular melodies. Without the foundations of patronage, tutelage, and the fostering of creative innovation, musical traditions can wither. Persian music is now threatened by the pressures of a mis-aligned market, a lukewarm government, and the all-embracing prescriptions of Western music theory. In the wider world of music, the 20th century has been unbelievably fruitful, but has suffered from the same prescriptions, and there are many alternatives that are left unexamined. These ghosts of the past and of the future will remain until we make the effort to listen.

More details on Iranian musical history can be found here: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3455/